Before the movies.

Before the merchandise.

Before the theme park, looming over—seriously—the local Muggle high school right across the street in Orlando.

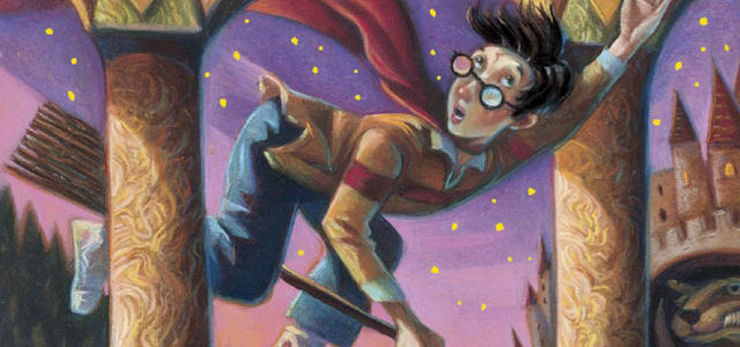

It was just a book, starting with a sentence about people who wanted desperately, frantically, to be normal.

What a perfect start for a series about people who aren’t normal at all—and a book about wanting desperately, frantically, to belong.

My copy of the book is the first American trade paperback edition, first printing, picked up about two weeks before the third book appeared in the U.S., after careful “translation” into American English. (The most alarming aspect of these edits was the assumption that American children would be unable to handle the concept of philosophers and would therefore need to be presented with sorcerers, but the American edition changes other small details as well, with Mrs. Weasley knitting, for example, sweaters and not jumpers. I rather wish the changes hadn’t been made; this series is intensely British, and was not improved by Americanization. But I digress.) A friend working at Barnes & Noble had told me that they were amusing, and noted that small children were already begging for the next book in the series. She thought it would turn out to be fairly popular.

That turned out to be a bit of an understatement.

By the time the fourth book arrived, the launch parties, the obsession, and the backlash had already begun, with the very popularity of the book itself inviting criticism.

But I didn’t know about any of that, or think about it when I sat down to read this first one. Instead, I found myself collapsing in laughter more than once.

That’s an odd thing to say about a book that has a brutal double murder in its opening chapter, immediately followed by a description of one of those hellish childhoods that British writers often do so well. Harry Potter, in the grand tradition of abused Roald Dahl protagonists, lives in a cupboard under the stairs, constantly terrorized by his cousin Dudley and abused by his aunt and uncle. Both, as it turns out, have reason: Uncle Vernon because he is hoping to turn Harry into someone “normal,” and Aunt Petunia for reasons that are revealed in a later book. But even this abuse is treated with humor, again in the grand Roald Dahl tradition, and although small children might be worried, adults are more likely to be grinning.

The humor and wordplay really swing into gear when Harry finally learns the truth—he’s not, as his uncle hoped would eventually happen, normal in the slightest, but rather a wizard. Of course, he’s going to have to learn how to do magic first. At Hogwarts.

Rowling’s trick of having Harry need the same introduction to magic and the wizarding world as readers do pays off remarkably well, since Harry can ask all the important questions about Quidditch, wizard money, cauldrons, wands, and so on. It helps that Harry, decidedly more of a jock than a brain, is not the best at figuring these things out on his own, needing someone—even, sometimes, his fellow Muggle-raised friend Hermione—to explain things to him, and thus, to readers. This allows Rowling’s infodumps—and I’d forgotten just how many this book has, not to mention all the sly details that become important later—to be inserted as just part of a dialogue, or conversation, adding to the friendly feel.

Rereading it now, several things struck me. First, I’m still laughing. Second, the sheer efficiency of Rowling’s prose here. Even things apparently thrown in as casual asides become desperately important later: the casual mention of Charley Weasley’s post-Hogwarts job as a dragon tamer. The phoenix feather inside Harry’s wand. Hagrid riding Sirius Black’s motorcycle. Harry’s cheerful conversation with a bored snake at the zoo. And, er, yes, the casual mention of a certain historian of magic and the way Harry swallows the Snitch in his second game—just to mention only a few of the references popping up later. Absolutely none of this seems important at the time, particularly on a first read, and yet, now that I’ve finished the entire series, I’m struck by how important it all was, and how few words are wasted here.

Third, I’m struck again by how well Rowling slyly integrated her mystery into the main book—so well, I must confess that I completely missed that the book even had a mystery until the last couple of chapters. I was reading for the jokes. After that, of course, I paid closer attention—but I’m glad I didn’t know when I first read this book; the surprise of finding a mystery was half the fun.

And more: the equally sly classical and medieval references. The immediate friendship that springs up between Harry and Ron, and the less immediate, but equally strong, friendship formed between the two of them and Hermione. (While I’m at it, kudos for showing that yes, boys and girls can be friends, even when the girl is extremely bossy, mildly annoying, and obsessive about tests.)

And, perhaps above all, just how fun this book is, even with the murders, the looming danger of He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named, and those ominous pronouncements by certain centaurs. After all, this is also a book where the chief monster is named Fluffy, a book where, in stark contrast to the rushing around of later books, the adventuring kids can stop for a nice chess game and a logic puzzle in their quest to defeat the bad guy.

I’m also surprised to find just how shadowy and insubstantial Voldemort is here, in more than one sense: we know he’s the bad guy, but that’s about it, and the various trappings of and references to Nazism and terrorism that enrich the later books are quite absent. Here, he’s only a possible threat. The real threats, as Dumbledore notes, are the internal ones: bravery versus cowardice, dreaming versus living.

That’s part of, I suppose, what makes this a remarkably reassuring book—true, Rowling has very real ghosts in her books, with the ability to throw things and make people feel decided chills, but they remain ghosts, unable to do true harm. And in some ways, their very presence lessens the fear of death, at least here: Harry can’t quite get his parents back, but he can see pictures of them waving at him. Rowling doesn’t offer the lie that death can be altered. But she does remind us that death doesn’t mean the end of memories.

Buy the Book

In An Absent Dream

And of course, by the end of the book, Harry Potter has found a place where he belongs, something that is almost (and eventually will be) a family. Finding this place wasn’t easy—nothing worthwhile ever is, I suppose—but it’s nice to have the reassurance that even in a world of evils and terrors and isolation, lonely children can find a place to belong and have friends. Even if this takes a little bit of magic. Especially since this reassurance would be a little less secure in later books.

Philosopher’s Stone draws on a wealth of British children’s literature—the idea, from Narnia and the Nesbit books, that magic can be found just around the corner, hidden behind the most ordinary of objects—a train station, a pub. From Roald Dahl (and others), the atrocious children and family life. And, yes, from that most banal of children’s authors, Enid Blyton, who provided some of the inspiration for school stories and children’s adventures. (It’s okay, Ms. Rowling; I read Enid Blyton too.) Rowling also litters her text with various classical and medieval references, some obscure, some obvious, and she was not the first to write tales of a wizardly school. But for all of the borrowing, the book has a remarkably fresh, almost bouncy feel.

Later books in the series would be more intricate, more involved, contain more moments of sheer terror and sharper social satire. But this book still remains one of my favorites in the series, partly for its warmth, partly for its mystery, partly for some of its marvelous lines. (“There are some things you can’t share without ending up liking each other, and knocking out a twelve-foot mountain troll is one of them.”) But mostly because this was the book that introduced me to Diagon Alley, to Platform 9 3/4, to Hogwarts, to Quidditch. And because of the sheer magic that gleams from its pages, the magic that makes me want to curl up again and again at Hogwarts, with a nice glass of pumpkin juice and cauldron cakes. Not Chocolate Frogs, though. With this sort of book, I don’t want anything jumping in my stomach.

An earlier version of this article appeared in June 2011.

Mari Ness currently lives rather close to a certain large replica of Hogwarts, which allows her to sample butterbeer on occasion. Her short fiction has appeared in Clarkesworld, Lightspeed, Fireside, Apex, Daily Science Fiction, Nightmare, Shimmer and assorted other publications—including Tor.com. Her poetry novella, Through Immortal Shadows Singing, was released in 2017 by Papaveria Press. You can follow her on Twitter at mari_ness.